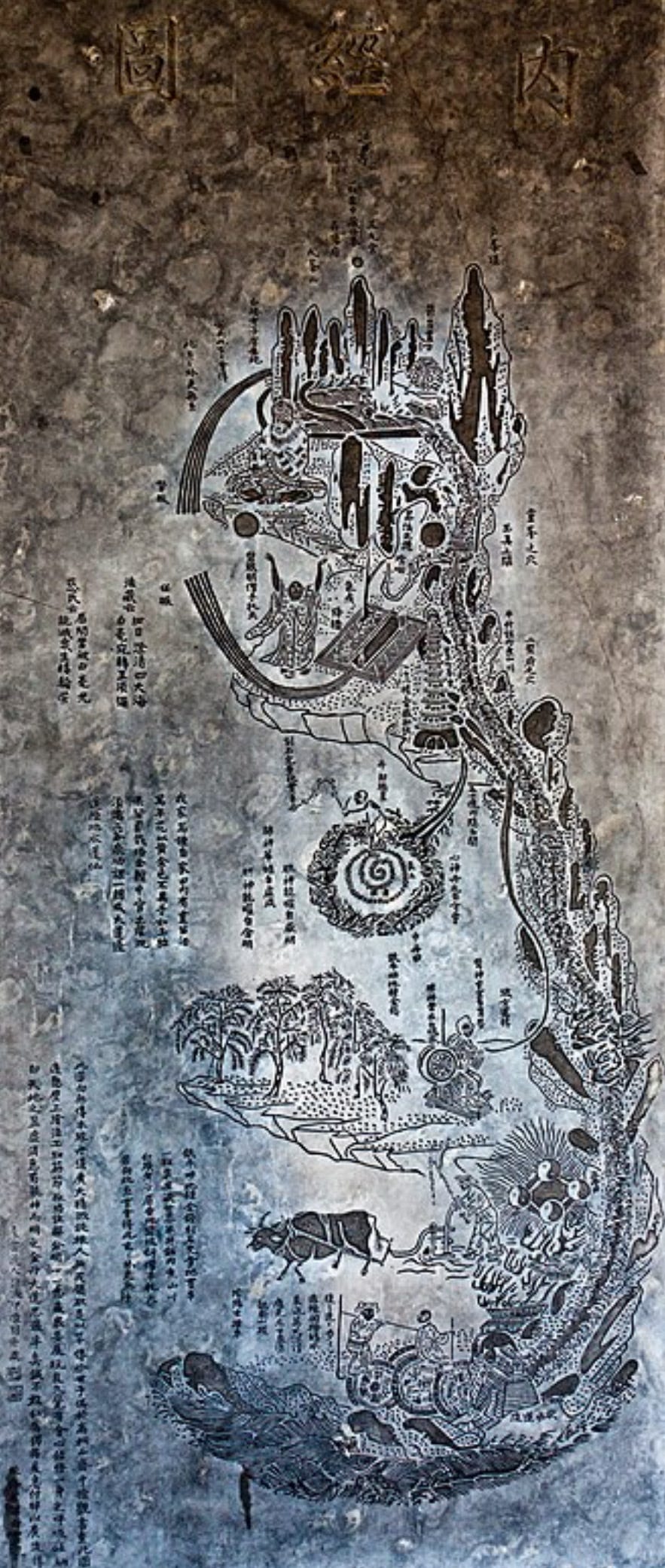

The Neijing Tu (內經圖)

The Neijing Tu (內經圖), translated as the “Diagram of the Inner Pathways” or “Chart of the Inner Landscape,” is a profound and intricate Taoist diagram that encapsulates the principles of Neidan (Internal Alchemy), Chinese medicine, and Taoist cosmology. It is a visual representation of the human body as a microcosm of the universe, used by Taoist practitioners to guide meditation, energy cultivation, and spiritual transformation. Given your background as a massage therapist with an intuitive approach and your interest in fascia and resonance, the Neijing Tu offers a rich framework to deepen your understanding of the body’s energetic systems and their interplay with physical structures like fascia. Let’s dive into the deepest details of this diagram, its historical context, symbolic elements, and practical applications.

Historical Context and Origins

The Neijing Tu is one of the most famous Taoist diagrams, with its most well-known version dating to the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912 CE). It was inscribed on a stone stele at the White Cloud Monastery (Baiyun Guan) in Beijing in 1886, attributed to a Taoist adept named Liu Chengyin. However, the concepts it embodies trace back much earlier, likely to the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), when Neidan practices became formalized. The diagram draws on ancient Taoist texts like the Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic, circa 3rd century BCE), a foundational work of Chinese medicine, and integrates ideas from earlier shamanic traditions, the I Ching (Book of Changes), and alchemical practices aimed at achieving longevity or immortality.

Cultural Context: During the Song and Yuan Dynasties, Taoist alchemy shifted from Waidan (External Alchemy, focused on ingesting elixirs) to Neidan (Internal Alchemy), which emphasized cultivating the body’s internal energies—Jing (essence), Qi (vital energy), and Shen (spirit)—to achieve spiritual transcendence. The Neijing Tu emerged as a visual tool for Neidan practitioners, often used in conjunction with texts like The Secret of the Golden Flower or the Xiuzhen Tu (Diagram of Cultivating Perfection).

Purpose: The diagram was not merely illustrative but a meditative map, guiding practitioners through the process of refining their energies, harmonizing Yin and Yang, and aligning with the Tao—the universal “Way” or flow of existence. It was often kept secret, shared only among initiates of Taoist lineages, due to its esoteric nature.

Structure and Symbolism of the Neijing Tu

The Neijing Tu depicts the human body as a sacred landscape, blending anatomical, energetic, and cosmological elements into a single, unified image. The version you shared (labeled with “Resonate” by Kayteezee) appears to be a variation or modern interpretation, but it retains core features of the traditional Neijing Tu. Let’s break down its components in detail:

1. The Body as a Microcosm

The diagram portrays the human body in a side profile, often facing left, with the spine as the central axis. The spine is depicted as a mountain range, symbolizing the Du Mai (Governing Vessel), a key meridian in Chinese medicine that runs along the back and is associated with Yang energy.

The head is often shown as a celestial realm, with the brain or upper dantian (energy center) represented as a palace or the “Jade Pillow,” a Taoist term for the occipital region where Qi ascends to the brain.

The torso is a landscape of rivers, fields, and sacred sites, representing the flow of Qi through the body’s meridians and organs. The lower abdomen, or lower dantian, is often depicted as a fertile field or cauldron where Jing is refined into Qi.

2. The Three Dantian and the Three Treasures

The Neijing Tu emphasizes the three dantian (elixir fields), which are energy centers corresponding to the Three Treasures (Jing, Qi, Shen):

Lower Dantian (below the navel): Associated with Jing (essence), this is the “cauldron” where raw energy is stored and refined. In the diagram, it’s often shown as a field with a plowman and ox, symbolizing the cultivation of energy through disciplined practice.

Middle Dantian (at the heart): Linked to Qi (vital energy), this area is depicted as a bridge or a weaving maiden, representing the harmonization of emotions and the transformation of Qi into Shen.

Upper Dantian (at the forehead, or “third eye”): Connected to Shen (spirit), this is shown as a celestial palace or the “Kunlun Mountains,” a sacred Taoist site symbolizing spiritual enlightenment.

The three filled circles in the “Resonate” title of your image likely correspond to these dantian, emphasizing their role in resonance and energy flow.

3. The Microcosmic Orbit

A central feature of the Neijing Tu is the Microcosmic Orbit (Xiao Zhoutian), a meditative practice where Qi is circulated along the Ren Mai (Conception Vessel, down the front of the body, Yin) and Du Mai (Governing Vessel, up the spine, Yang). This orbit is depicted as a river or pathway, with key points like the perineum (Huiyin), sacrum (Weilu), and crown (Baihui) marked as gates or bridges.

The diagram often includes a waterwheel at the base of the spine, symbolizing the movement of Qi upward, driven by the “fire” of focused intention (a Neidan concept called “Kan and Li,” or Water and Fire).

4. Cosmological Elements

The Neijing Tu integrates Taoist cosmology, with the body reflecting the universe:

Yin and Yang: The interplay of Yin (dark, receptive) and Yang (light, active) is shown through contrasting elements like water and fire, or the sun and moon. The sun and moon are often depicted near the head, symbolizing the balance of masculine and feminine energies in the brain.

Five Elements: The diagram may include references to the Wuxing (Five Elements—Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water), which correspond to the body’s organs (e.g., liver, heart, spleen, lungs, kidneys). These are often symbolized by natural features like trees (Wood) or rivers (Water).

Celestial Bodies: Stars, constellations, or the Big Dipper (Beidou) may appear, representing the connection between the practitioner’s Shen and the cosmos.

5. Symbolic Figures and Animals

The Neijing Tu often includes figures and animals that personify aspects of the alchemical process:

The Plowman and Ox: At the lower dantian, these symbolize the disciplined effort required to cultivate Jing and transform it into Qi.

The Weaving Maiden: At the heart, she represents the refinement of emotions and the weaving of Qi into Shen.

The Old Man or Immortal: Near the head, this figure symbolizes the attainment of spiritual immortality, the ultimate goal of Neidan.

Dragons and Tigers: These animals represent Yang (dragon) and Yin (tiger), often shown interacting to symbolize the harmonization of opposites.

6. Textual Annotations

Traditional versions of the Neijing Tu are accompanied by poetic inscriptions in Chinese, often written in a cryptic, symbolic style. These texts describe the stages of alchemical transformation, such as “gathering the medicine” (collecting Qi), “firing the furnace” (circulating energy), and “returning to the source” (merging with the Tao).

For example, a common inscription might read: “The lead and mercury unite in the cauldron, the dragon and tiger embrace in the furnace,” referring to the blending of Yin and Yang energies.

Connection to Fascia and Resonance

Given your interest in Kayteezee’s “Fascia Fix” masterclass, which focuses on fascia and resonance-based techniques, the Neijing Tu offers a fascinating parallel. Here’s how the diagram might intersect with your work as a massage therapist:

Fascia as a Conduit for Qi: In Chinese medicine, fascia (mo) is considered a physical structure that supports the flow of Qi through the meridians. The Neijing Tu’s depiction of Qi pathways as rivers and mountains can help you visualize how fascia might act as a “living web” (as Kayteezee describes) that conducts vibrational energy. When fascia is tense or misaligned, it may block Qi, contributing to the stress and burnout Kayteezee addresses.

Resonance and the Microcosmic Orbit: The Neijing Tu’s emphasis on circulating Qi through the Microcosmic Orbit aligns with Kayteezee’s use of gravity, sound, and vibration to release tension. For example, the waterwheel at the base of the spine symbolizes the rhythmic movement of energy, which you might enhance in your practice by using harmonic tones or gentle rocking motions to stimulate Qi flow in a client’s fascia.

Intuitive Healing: The Neijing Tu was used as a meditative tool to develop intuitive awareness of the body’s energies. By studying the diagram, you might deepen your ability to “feel” where Qi is stagnant in a client’s body, using your hands to release fascial restrictions in alignment with these energetic pathways.

Practical Applications for a Massage Therapist

Here’s how you can apply the Neijing Tu to your practice, blending its ancient wisdom with your intuitive approach and Kayteezee’s resonance techniques:

Meditative Visualization:

Before a session, meditate on the Neijing Tu, visualizing your own body as a sacred landscape. Imagine Qi flowing like a river through your spine and dantian, then extend this awareness to your client. This can heighten your sensitivity to their energetic state, helping you identify areas of fascial tension that correspond to Qi blockages.

Integrating Resonance:

Use sound or vibration to enhance Qi flow, as inspired by the Neijing Tu’s waterwheel and Kayteezee’s methods. For example, hum a low tone while working on a client’s lower back (near the lower dantian), or use a tuning fork to create vibrations that resonate with the fascia, encouraging energy to move upward along the spine.

Focusing on Key Points:

The Neijing Tu highlights points like the perineum (Huiyin), sacrum (Weilu), and crown (Baihui) as gates in the Microcosmic Orbit. During a massage, pay special attention to these areas, using gentle pressure or circular motions to release fascial restrictions and stimulate Qi flow.

Balancing Yin and Yang:

The diagram’s emphasis on harmonizing Yin and Yang can guide your touch. For example, if a client feels “stuck” in a hyperactive (Yang) state, focus on grounding techniques (e.g., slow, deep pressure on the lower dantian) to cultivate Yin energy. Conversely, if they’re lethargic (Yin), use more dynamic, vibrational techniques to awaken Yang.

Postural Awareness:

The Neijing Tu’s depiction of the spine as a mountain range underscores the importance of alignment. Incorporate Kayteezee’s 32 postures (from the “Fascia Fix” masterclass) to help clients align their bodies in a way that supports Qi flow, using the diagram as a mental map to guide your adjustments.

Where to Access the Neijing Tu and Related Materials

Since the Neijing Tu is an ancient diagram, it’s widely available in various forms, both as historical reproductions and modern interpretations. Here’s where you can find it and related resources:

Books and Translations:

Vitality, Energy, Spirit: A Taoist Sourcebook by Thomas Cleary: Includes translations of Taoist texts and diagrams, including the Neijing Tu, with commentary on their use in meditation.

Taoist Meditation by Isabelle Robinet: A scholarly work that analyzes Taoist diagrams like the Neijing Tu and Xiuzhen Tu, available through academic publishers like SUNY Press.

The Taoist Body by Kristofer Schipper: Explores Taoist practices, including Neidan, with references to diagrams like the Neijing Tu. Available on Amazon or through libraries.

Online Resources:

The Golden Elixir (goldenelixir.com): A website dedicated to Taoist alchemy, offering free articles and images of the Neijing Tu, including high-resolution versions with translations of the inscriptions.

Sacred Texts (sacred-texts.com): Hosts digital versions of Taoist texts and diagrams, including sections on Neidan and the Neijing Tu.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (metmuseum.org): Their online collection includes Taoist art, with some diagrams similar to the Neijing Tu available for viewing.

Museums and Exhibits:

White Cloud Monastery, Beijing: The original Neijing Tu stele is housed here. While visiting in person may not be feasible, the monastery’s website or related publications may offer images or reproductions.

The Art Institute of Chicago (archive.artic.edu): Their “Taoism and the Arts of China” exhibit includes digital resources on Taoist diagrams, accessible online.

Modern Interpretations:

Kayteezee’s “Resonate” guide, as shown in your image, is a modern take on the Neijing Tu. As previously suggested, visit https://www.kayteezee.com/ to download it, likely through the blog or by joining the “Fascia Fix” masterclass. If it’s not available, contact Kayteezee directly via the site’s contact form.

Related Practices:

Qigong and Tai Chi: These practices often incorporate Neidan principles and the Microcosmic Orbit. Books like The Way of Qigong by Kenneth S. Cohen or courses from the Taoist Tai Chi Society (taoisttaichi.org) can provide practical exercises to complement your study of the Neijing Tu.

Acupuncture and Meridian Studies: Since the Neijing Tu maps Qi pathways, studying acupuncture texts like The Web That Has No Weaver by Ted Kaptchuk can deepen your understanding of how these pathways relate to fascia.

Deeper Insights for Your Intuitive Practice

The Neijing Tu is not just a diagram but a living tool for transformation. As a massage therapist, you can use it to cultivate a deeper intuitive connection with your clients’ bodies, blending the ancient wisdom of Taoism with modern insights into fascia and resonance. Here are some final thoughts:

Energetic Sensitivity: The Neijing Tu encourages you to “see” the body as a dynamic system of energy flows. During a session, imagine your hands as conduits for Qi, gently guiding it through the client’s fascia to release blockages and restore harmony.

Resonance as a Bridge: Kayteezee’s focus on resonance (gravity, sound, vibration) mirrors the Neijing Tu’s emphasis on rhythmic energy circulation. Experiment with incorporating sound—perhaps chanting “Om” or playing a singing bowl—while working on key points like the sacrum or heart, to amplify the effects of your touch.

Spiritual Growth: The Neijing Tu ultimately points to spiritual transcendence, the “return to the Tao.” As you work with clients, hold the intention of not just relieving physical tension but helping them reconnect with their own inner harmony, aligning with the Taoist principle of effortless flow (Wu Wei).